A new United Nations (UN) report on worldwide drug trends acknowledges that marijuana legalization in the U.S. and Canada may have helped to shrink the size of illicit markets, while at the same time driving significant drops in the number of people arrested for cannabis offenses. It also notes the emergence of what it calls a “psychedelic renaissance.”

“In some jurisdictions, the the size of the illegal cannabis market appears to be shrinking,” say key findings of the 2024 World Drug Report, from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), “and in the United States the number and rate of people arrested for cannabis-related offences [appears] to be decreasing.”

At the same time, sharp racial disparities in marijuana arrests have persisted even as raw arrest numbers drop, and legalization has also popularized new forms of marijuana products that raise concerns about youth use, including vapes, high-THC cannabis concentrates and infused edibles, the UN office says.

As of the beginning of 2024, a number of UN member states—Canada, Uruguay and 27 jurisdictions in the U.S.—had “enacted legal provisions allowing the production and sale of cannabis for non-medical use,” the report says, while others, such as in Europe, “offer varying degrees of regulated access to cannabis for non-medical use.”

The report “is aimed not only at fostering international cooperation to counter the impact of the world drug problem on health, governance and security,” a UNODC press release says, “but also at assisting Member States in anticipating and addressing threats posed by drug markets and mitigating their consequences.”

A map of “The World Drug Problem” included in the report does not specifically call out marijuana in any global region, though it says that “cannabis trafficking and use affect all regions worldwide.” Primarily, however, the report looks at other drugs, such as opioids, methamphetamine, cocaine and newer synthetic substances.

UN Office on Drugs and Crime

The document also highlights that “a renewed interest in the therapeutic use of different psychedelic substances—controlled under the international drug conventions — for the treatment of a range of mental health disorders has sparked a wave of clinical trials.”

“Results from the early stages of ongoing medical research have led to policy changes that have allowed access to psychedelics for ‘quasi-therapeutic’ use in a couple of jurisdictions in the United States as well as for medical use in Australia and one jurisdiction in Canada,” it says.

“Within the broader ‘psychedelic renaissance’, there are popular movements that are distinct from traditional use by Indigenous communities and are contributing to burgeoning commercial interest and to the creation of an enabling environment that encourages broad access to the unsupervised, ‘quasi-therapeutic’ and non-medical use of psychedelics,” UNODC adds elsewhere in the report, noting that “the impulse to legalize psychedelics seems to be motivated more by the desire for unsupervised therapeutic use within the overall realm of mental health, mindfulness, spirituality and overall well-being.”

UN Office on Drugs and Crime

As for cannabis, which UNODC calls in the new report “by far the world’s most commonly used drug,” an estimated 228 million people globally used the substance, representing about 4 percent of the world’s population. In North America, the region where marijuana use is the most popular, nearly 1 in 5 people (19.8 percent) between 15 and 64 used the drug in 2022.

Regarding medical marijuana, UNODC said there’s evidence “of the effectiveness of cannabinoids in treating a few conditions, but for many others the evidence is limited.”

“Many countries have made provisions for the medical use of cannabis,” it added, “but the regulatory approaches to medical cannabis differ widely among those countries.”

The UN report also says that “new means of drug delivery are negatively impacting young people,” noting that harmful marijuana use among adolescents “remains a concern in many regions.”

“While daily cannabis use among adolescents in North America remains stable, there has been an increase in the regular vaping of cannabis,” the report says among its key findings. “The availability of vapes, concentrates, and edibles post-legalization may have increased the overall health harm of cannabis.”

It says hospitalizations related to marijuana have increased, “particularly for cannabis-induced psychosis and withdrawal, with young adults being disproportionately affected.”

“While all age groups benefit from prevention programmes,” the report says of drug use generally, “prioritizing children and young people is crucial. Adolescence is a peak period for initiating substance use, as it is a time when brain development is still ongoing.”

Looking at substance trends worldwide, the UN report also notes that “the gap is widening” between the number of people people who have substance use disorders and the number of people actually receiving treatment.

“Only about 1 in 11 people with drug use disorders received drug treatment globally in 2022,” it says, “a decrease from 2015.” Treatment gaps were widest in Africa and Asia, and treatment coverage was also lower among women in all five global regions.

In most areas, people in treatment were primarily in treatment for opioids (Americas, Europe) or amphetamines (Asia, Oceania), while cannabis was the most common primary drug for people in treatment in Africa. Cannabis use is also growing the fastest in Africa compared to other regions, the report says.

Nevertheless, the report says, marijuana “accounts for a substantial share of drug-related harm globally, owing in part to its high prevalence of use.” Citing 2019 data, it continues that “an estimated 41 per cent of drug use disorder cases globally are cannabis use disorders.”

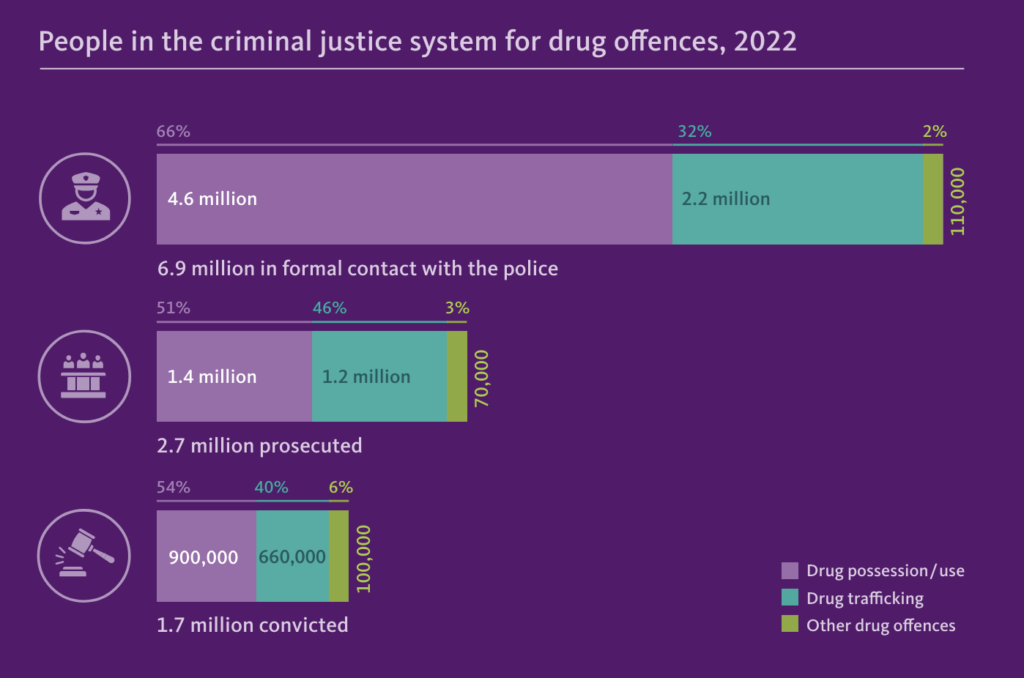

Globally, simple drug use and possession also “continue to bring the most people into contact in the law,” the UNODC report says. In 2022, for example, roughly 7 million people across the world were in contact with police over drug offenses, “with about two thirds of this total due to drug use or possession for use.”

In most global regions, the likelihood of prosecution and conviction were lower for possession and use compared to trafficking offenses, but the opposite was true in Africa and Asia, where “people arrested for drug use or possession are more likely to be prosecuted and convicted than those arrested for drug trafficking.”

UN Office on Drugs and Crime

“While the rate of persons arrested for drug use or possession offenses in the Americas is one of the highest”—second only to Europe—”the region has the lowest rate of conviction for such offenses.”

Globally, nearly 9 in 10 people arrested on drug offenses in 2022 were men. “Women account for some 9 per cent of those arrested for drug trafficking,” the report says, “and for 12 per cent of those arrested for drug use or possession.”

The UNODC report was published Wednesday, just days after a separate, human rights-focused UN document urged member states to abandon the war on drugs. Tlaleng Mofokeng, the UN’s special rapporteur on the right to health, urged member nations in the new report to end the war on drugs and instead enact harm-reduction policies such as decriminalization, supervised consumption sites, drug checking and widespread availability of overdose reversal drugs like naloxone—while also moving toward “alternative regulatory approaches” for currently controlled substances.

Among that report’s recommendations is that countries “decriminalize the use, possession, purchase and cultivation of drugs for personal use and move toward alternative regulatory approaches that put the protection of people’s health and other human rights front and centre.”

Mofokeng, who is also a medical doctor and professor at Georgetown University’s Law School, urged that leaders “move from a reliance on criminal law and instead take a human rights-based, evidence-based and compassionate approach to harm reduction in relation to drug use and drug use disorders.”

The nonprofit human rights group Amnesty International also recently put out a report calling for the legalization of all drugs, part of a health- and harm reduction-focused approach to regulation.

Late last year, meanwhile, 19 Latin American and Caribbean nations issued a joint statement acknowledging the need to rethink the global war on drugs and instead focus on “life, peace and development” within the region.

A report last year from an international coalition of advocacy groups, meanwhile, also found that global drug prohibition has fueled environmental destruction in some of the world’s most critical ecosystems, undermining efforts to address the climate crisis.

And a year ago, UN special rapporteurs in a separate report said that “the ‘war on drugs’ may be understood to a significant extent as a war on people.”

“Its impact has been greatest on those who live in poverty,” they said, “and it frequently overlaps with discrimination directed at marginalised groups, minorities and Indigenous Peoples.”

In 2019, the UN Chief Executives Board (CEB), which represents 31 UN agencies including the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), adopted a position stipulating that member states should pursue science-based, health-oriented drug policies—namely decriminalization.

Marijuana Moment Read More