I am staring ahead at two tigers leaping through the sky, approaching a naked woman who is lying blissfully unaware on a floating block of ice. It is Dali’s famous 1944 painting, succinctly titled, “Dream Caused by the Flight of a Bee Around a Pomegranate a Second Before Awakening.”

A year before this painting was completed, on April 19, 1943, Swiss chemist Albert Hofmann first ingested LSD and discovered its psychedelic properties.

I looked on at this painting and wondered what has shaped the psychedelic art evolution. How did we go from the surrealist movement that began in the early 1920s, with Magritte and Miro, to Alex and Allyson Greys’ Chapel of Sacred Mirrors, or Beeple’s social commentary through absurd imagery? How has our mode of consuming this very art changed – from psychedelic rock posters and albums of the 1960s to trippy images produced for Instagram? How has the art of Indigenous cultures influenced and shaped the art we turn to today?

First, I want to define what we mean by “psychedelic art.” Any piece of artwork can feel psychedelic. If you take a tab of acid and head to an art museum, that will certainly help. But what makes a piece feel inherently psychedelic relies on two factors: the distinctive, uniquely colorful style and composition, as well as the feeling that arises from a familiar idea or reality being subverted. It forces you to look at the world, as well as yourself, from a new perspective, and feel more deeply connected to the universe around you.

READ: Everything to Know About LSD Art

So, how is this art created? Artist Allyson Grey tells me, “a psychonaut may have a vision filled with brilliance and personal meaning and may feel compelled to mark that essential visionary moment in a work of creativity. If they are skilled, the portrayal may be considered great Visionary or Psychedelic Art.” The term, “Visionary Art” is the broader category, she explains, as it “describes art that depicts a person’s Mystical Encounter, an unforgettable meeting with the Divine. The earliest artwork, cave art, reports ancient brushes with visionary realms.”

British psychologist and researcher Humphry Osmond coined the term “psychedelic” in 1956 at a meeting of the New York Academy of Sciences, describing the word to mean “mind-manifesting.” The word comes from the Greek words psyche (mind) and delos (manifest), implying that psychedelics can reveal the human mind’s unused potential. By that definition, all artistic efforts to depict the inner world of the psyche may be considered “psychedelic.”

But psychedelic art has deep roots in the artistic and spiritual traditions of many Indigenous cultures, long before the term “psychedelic” even first came into use.

Psychedelic Art Traditions within Indigenous Cultures

In Indigenous cultures in Peru, Brazil, Colombia, and Ecuador, there is art centered around Ayahuasca, which features complex geometric patterns and shapes representing the interconnectedness of life. Amazonian tribes, like the Shipibo-Conibo of Peru, create intricate visual patterns that reflect the visions and insights gained during ayahuasca ceremonies. The patterns represent the “Icaros” (healing songs) sung by shamans during ceremonies and are seen as a form of communication with the spirit world.

Pablo Amaringo, a shaman and celebrated artist, was renowned for his vibrant paintings depicting his ayahuasca visions, which include spirits, animals, and cosmic landscapes.

Another Peruvian artist, Geenss Archenti, combines light-filled patterns with an earthy feel by using natural pigments he prepares from trees and medicinal plants. Archenti often paints on handmade banana leaf paper.

“Growing up in the Amazon jungle, surrounded by nature’s vibrant life, deeply influenced my artistic journey,” Archenti tells me. “My upbringing taught me to honor nature, to see its interconnectedness, and to express that in my art. The spirituality of the jungle and its ancient traditions are embedded in every brushstroke, guiding me toward a deeper understanding of both nature and self.”

READ: Pablo Amaringo Drank Ayahuasca at 10 Years Old, Then Ushered In a Global Art Tradition

Other cultures, of course, differ in their artistic styles. The Huichol people of Mexico use beadwork, yarn painting, and embroidery to create images inspired by peyote visions, which often include animals, like deer and eagles, and scenes of gods and ancestors. Yarn paintings (called nierika) are a common form of artistic expression and serve as sacred offerings.

Native Americans in the United States incorporate art that includes beadwork, painted drums, and ceremonial items used in peyote rituals. Ceremonial objects like fans, gourds, and feathers are often decorated with beadwork that reflects visions and spiritual guidance received during ceremonies.

The San People of South Africa’s rock art often depicts shamanic trance states, with images of healers, dancing, animals, and abstract patterns. These rock paintings, some of which are thousands of years old, are believed to represent visions experienced during trance states. San rock paintings in places like the Drakensberg Mountains depict a range of subjects, from animals and human figures to abstract forms that evoke altered states of consciousness.

For Aboriginal Australians, dot paintings are deeply connected to their spiritual beliefs. The dot patterns, earthy colors, and symbolic depictions of landscapes and animals represent “Dreamings” or stories that hold spiritual and cultural significance. Symbols include concentric circles (representing water holes or gathering spots) and U-shapes (indicating people sitting).

From Dreams to Drugs

In the Western world, while the inspiration for surrealism was defined through the observance of dreams, drug-induced hallucinations helped serve as the inspiration for psychedelic art. If the surrealists were fascinated by Freud’s theory of the unconscious, the psychedelic artists were moved by Albert Hofmann’s discovery of LSD.

In the 1950s, early artistic experimentation with LSD was conducted in a clinical context by Los Angeles–based psychiatrist Oscar Janiger. Janiger asked a group of different artists to each do a painting from the life of a subject of the artist’s choosing. They were then asked to do the same painting while under the influence of LSD. The two paintings were compared by Janiger and also the artist. The artists almost unanimously reported LSD to be an enhancement to their creativity. Eventually, around the late 1950s into early 1960, psychedelic art started to gain popularity through new forms.

The Counterculture Movement of the 1960s

The Beatniks recognized the role of psychedelics in Native American religious ritual, and identified with this desire to disorient the senses and go inward in their work. The Yage Letters (1963), written by William S. Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg, is a collection of correspondence and chronicles Burroughs’ visit to the Amazon rainforest in search of ayahuasca.

San Francisco artists such as Rick Griffin, Victor Moscoso, Bonnie MacLean, Stanley Mouse & Alton Kelley, Bob Masse, and Wes Wilson soon gained traction with their psychedelic rock concert posters. This new style drew from Art Nouveau, Surrealism, and Eastern spiritual imagery. Bright, saturated colors, swirling patterns, mandalas, and kaleidoscopic imagery started being incorporated, and their work was immediately influential for vinyl record album cover art as well.

This style developed internationally and spread out from San Francisco. British artist Bridget Riley became famous for her OP art paintings of psychedelic patterns that created optical illusions. Mati Klarwein created psychedelic masterpieces for Miles Davis’ Jazz-Rock fusion albums.

READ: Alice Coltrane’s Journey to Satchidananda

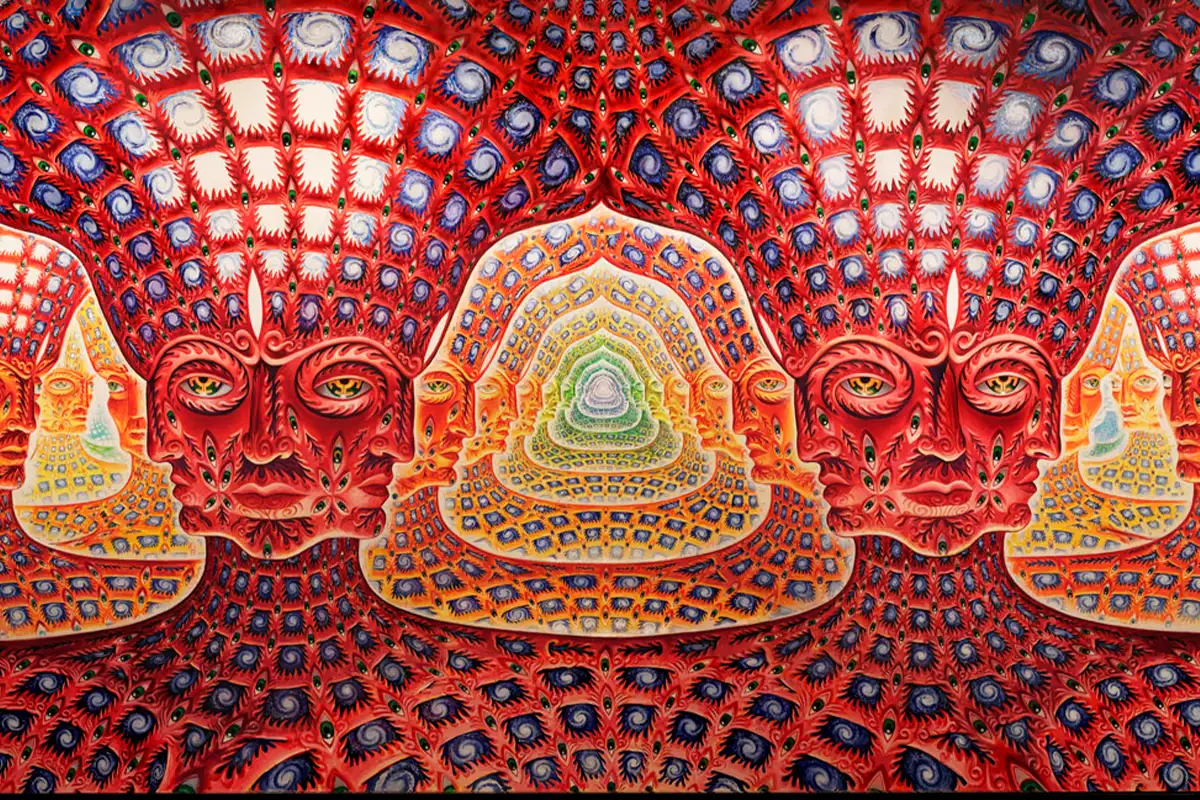

“The first Psychedelic Art I ever saw was in Life Magazine September 9, 1966, with a cover feature on LSD ART,” Alex Grey muses. Grey is a well-known visual artist, author, and community leader known for creating spiritual and psychedelic artwork, such as his 21-painting Sacred Mirrors series.

“I was 12 years old and totally fascinated. That article focused on trippy environments and light shows, revealing that Psychedelic Art meant expanded media as well as drawing and painting. One of the painters featured in the Life article was Allen Atwell, who had painted his entire apartment in New York City in 1965. It’s a hot mix of biomorphic and gestural forms, with brightly pigmented shapes completely covering walls and ceilings. He would trip and let loose. Unfortunately, he had to paint it out because it was a rented apartment and the landlord did not approve!”

Light Shows & Blotter Art

Psychedelic light-shows began to be developed for rock concerts. Using oil and dye in an emulsion that was set between large convex lenses upon overhead projectors, light show artists created bubbling liquid visuals that pulsed in rhythm to the music. This was mixed with slideshows and film loops to create a motion picture art form to visually represent the improvisational jams of the rock bands and create a trippy atmosphere for the audience. The Brotherhood of Light was responsible for many of the iconic light shows at rock concerts in San Francisco, and performed over 2,500 shows worldwide.

Blotter Art

Psychedelic art was eventually applied to the LSD itself. LSD began to be put on blotter paper in the early 1970s, giving rise to blotter art, a specialized art form for decorating blotter paper. Often, the blotter paper was decorated with tiny insignia on each perforated square tab, but by the 1990s, this had progressed to complete four-color designs. Mark McCloud, the visionary behind the “Institute of Illegal Images,” became a recognized authority on the history of LSD blotter. A photographer, sculptor, painter, art teacher, and amateur comedian, he was the preeminent collector of LSD blotter paper art and owed an estimated 33,000 sheets of paper bearing miniature artworks.

A New Style Is Born

Color juxtaposition became a primary characteristic within Psychedelic Art, as it led to the formation of other optical illusions and geometric lines. Other major characteristics found within the Psychedelic aesthetic were spirals that seemed kaleidoscopic in nature, concentric circles, paisley patterns, and repetitions of motifs or symbols until a pattern was formed. Collages were also an important component.

By the mid-1970s, the psychedelic art movement had become so popular that it was largely co-opted by mainstream commercial forces and advertising, incorporated into the very system of capitalism that the hippies had struggled so hard to change.

Psychedelic Art became more toned down, as the entire movement was assimilated by the cultural industry. Psychedelic Art of the 1970s was more ironic than it was revolutionary, as its infamous kaleidoscopic color palettes and trippy art images slowly morphed into representing the commodities advertisers were attempting to sell.

The Rise of Psychedelic Fantasy and Science Fiction Art in the 1970s

In the 1970s, psychedelic art increasingly merged with fantasy and science fiction themes, genres that were growing in popularity. Artists such as Roger Dean became known for surreal, alien landscapes on album covers, especially for progressive rock bands like Yes and Asia. His otherworldly creatures and dreamscapes carried the psychedelic aesthetic into a more cosmic, speculative realm.

As rock music evolved into genres like hard rock, heavy metal, and prog rock, album art reflected these darker, more intense styles. Artists like Hipgnosis created iconic covers for bands like Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin, and Black Sabbath, often incorporating surreal and experimental imagery that suggested altered states and psychological exploration.

This new style gradually led to the underground comix movement. Illustrator, musician, and “comic stripper” Brian Blomerth is the heir apparent to the underground comix scene of the ‘60s and ‘70s. You’ll recognize his signature dog-human hybrids traversing Technicolor scenes rooted in pharmacological history.

Artists like Moebius (Jean Giraud) in France combined sci-fi themes with intricate, often trippy linework in comic books like The Airtight Garage and Arzach. Films like Fantastic Planet (1973) were created, and this style influenced both the psychedelic art scene and the larger visual culture of the decade, contributing to the rise of graphic novels as a serious art form. Typography and graphic design from this era maintained psychedelic influences, with warped fonts, intricate linework, and vibrant colors.

The Dawn of Digital Art and Animation in the 1980s

The 1980s saw the first experiments in digital art, with artists using computer graphics to create surreal imagery. This period laid the groundwork for the future of digital psychedelia, as artists began exploring fractals and geometric patterns generated through early computer programs. Psychedelic aesthetics soon began to influence video game graphics and animation.

Neon colors, geometric shapes, and surreal landscapes became a staple in early arcade games and animations, like Tron (1982) and Heavy Metal (1981), which featured futuristic visuals. Later on, more animated, dystopian films were being made, such as Akira (1988).

The resurgence of interest in vintage and Art Deco styles also brought psychedelic aesthetics back into graphic design, but with a sleeker, polished feel typical of 1980s style.

Fractals, discovered by mathematician Benoît Mandelbrot in the late 1970s, became a popular visual motif. Fractals’ repeating, intricate patterns and self-similar designs made them visually psychedelic, evoking the organic, kaleidoscopic forms seen in traditional psychedelic art. They became especially influential in early computer-generated art and visualizations that explored mathematical beauty.

Rave Culture and the Digital Revolution in the 1990s – 2000s

The rise of electronic dance music brought psychedelic art back into focus through the rave scene. Fluorescent colors, mandalas, and fractals were central themes in art used for festival posters, event flyers, and club decor. Computer-generated imagery and digital tools allowed artists to experiment with 3D models and infinite looping animations, pushing the boundaries of psychedelic visuals. Films such A Scanner Darkly (2006) and Enter the Void (2009) were produced, the former using rotoscoping, and the latter using pulsating lights and eerie CGI fractals.

The development of psychedelic imagery for virtual and augmented reality began, providing immersive, interactive, and multi-sensory experiences that deeply resonated with the theme of altered perception. Graphic software began developing at a fast pace, which allowed the digital recreation of psychedelic experiences to become a possibility.

The development of two-dimensional and three-dimensional graphics allowed unparalleled freedom. Suddenly, even amateur artists had access to the technology needed to create digital art, which broadened the accessibility of the movement entirely.

Neo-Psychedelic Art of the 2010s

With the rise of digital media, social platforms, and immersive experiences, the 2010s saw a new wave of “neo-psychedelic” artists who used technology to expand on the traditional themes of altered consciousness, nature, and mysticism. This period also aligned with a revival of interest in psychedelics within scientific research, psychotherapy, and wellness, influencing the art scene.

Artists in the 2010s used advanced digital tools, including VR, 3D modeling, and fractal software, to create intricate, immersive visuals that evoked psychedelic states. Platforms like Adobe Photoshop, Blender, and custom fractal software allowed for a new level of detail and experimentation, resulting in complex, layered compositions that were visually dense and surreal.

Fractal algorithms and sacred geometry created compositions that mirrored patterns found in nature, such as flowers, shells, and crystals, evoking themes of unity, the interconnectedness of life, and cosmic order.

Merging Art with Technology

Platforms like Instagram, Tumblr, and DeviantArt provided a space for psychedelic artists to reach global audiences, making it easier than ever to share and view neo-psychedelic work.

The emergence of blockchain technology and NFTs opened up new avenues for artists to create, share, and sell digital art. Artists like Beeple and Android Jones became early adopters, releasing limited-edition pieces that resonated with both the art and tech communities.

Android Jones became known for his complex digital paintings, VR experiences, and live projection mapping. Jones’s work explored themes of consciousness, spirituality, and transformation. His Microdose VR platform offered interactive psychedelic experiences in virtual reality.

Beeple started creating surreal digital artwork. Known for his Everydays project, Beeple’s works often mixed vibrant, psychedelic visuals with political and social commentary, highlighting the surreal and often absurd aspects of contemporary life.

Combining traditional and digital media, Simon Haiduk made visually intense, nature-inspired artworks that explore the connection between humans and nature. His work often features animals, forests, and cosmic landscapes that evoke themes of interconnectivity and the life force.

Sabrina Ratté, a Canadian multimedia artist living in Montreal, uses mesmerizing and abstract animations, videos, and photos often incorporating “glitch” aesthetics and digital manipulations.

Don Mupasi, a U.K.-based 3D visual artist and photographer from Zimbabwe, amassed a large following for creating striking retro sci-fi 3D animations and NFTs under the alias Visualdon.

Psychedelic Art at Festivals

Psychedelic art flourished at festivals such as Burning Man, Lightning in a Bottle, and Boom Festival, which became showcases for large-scale installations and immersive art, such as Christopher Shardt’s Mariposa, the Shrumen Lumen by FoldHaus Art Collective, and installations by Luke Brown.

Meow Wolf became established as a space to spotlight highly interactive art, featuring kaleidoscopic environments and narrative-driven spaces, such as this winding tunnel of eggs by Burt Vera Cruz. Other spaces also offer immersive experiences, such as the Artechouse Gallery in New York City, Electric Ladyland in Amsterdam, and the Mori Building, Tokyo’s first digital art museum.

Another way psychedelic art has recently been brought to life is through “Hallucinariam,” a musical performance experience inspired by the mystical art of Alex & Allyson Grey. The stage, alive with vibrant sculptural beings and hypnotic backdrops, reflects the interconnectedness and sacred geometries associated with the Greys’ art.

Blacklight art also had a resurgence, especially at festivals. Alex Aliume is known for his vibrant, cosmic-inspired, and UV glow-in-the-dark artwork. His creations are influenced by sacred geometry, mysticism, and themes of universal interconnectedness. Aliume combines light, motion, and three-dimensional elements in his work, often using blacklight to create immersive experiences.

“Creators are increasingly experimenting with fluorescent mediums, building moving kinetic sculptures, and turning their rooms and offices into blacklight temples,” says Aliume. “When I first started, there was almost no UV art, let alone in art galleries. People even told me that “blacklight art” had died in the ’60s… Now, I carry its spirit in a new form, bringing it to the big stage. Visionary art is not about “hippie stuff” or simply “trippy bright colors.” It represents the inevitable and necessary evolution of human consciousness.”

Evolving to Present Day

Contemporary psychedelic artists worldwide continue to explore and push boundaries with mind-expanding, surreal, and immersive visuals. One can find this style in modern TV shows such as Adventure Time, an animated series that delves into dreamlike sequences, or Midnight Gospel, Pendleton Ward, and Duncan Trussell’s animated series that combines philosophical musings with trippy visuals.

Modern artists shape psychedelic art’s role in modern culture, blending aesthetic exploration with themes of self-awareness, transformation, and interconnection. This art can now be found from our screens to the street murals around us.

Lauren YS

Lauren YS is a non-binary artist based in Los Angeles who creates colorful and surreal work influenced by dreams, mythology, psychedelia, love, sex, and their Asian-American heritage. Their otherworldly creatures transport viewers to the wild workings of the artist’s mind.

Alex & Allyson Grey

Alex Grey’s paintings are known for their anatomical precision combined with spiritual and psychedelic themes. His works often feature transparent human bodies displaying energy systems and connections to higher consciousness. He and his wife Allyson Grey run the Chapel of Sacred Mirrors (CoSM), an art sanctuary dedicated to the mystical experience.

Though they gained prominence in earlier decades, Alex and Allyson Grey’s influence grew in the 2010s. Their Chapel of Sacred Mirrors (CoSM) provided a physical and spiritual space for psychedelic and visionary art, serving as an inspiration for many younger artists.

Amanda Sage

A visionary artist known for her vibrant paintings that explore the intersection of humanity, nature, and the cosmos. Sage often uses a glazing technique, layering thin layers of paint to create glowing, otherworldly scenes. Some of her best known work is “Gaia Awakening,” “Keeper of the Light,” and her series of portraits that explore self-transformation.

Chris Dyer

Dyer’s vibrant, multicultural art blends skate culture, spirituality, and psychedelic themes. He uses traditional media like paint, wood, and markers to create intricate murals, posters, and skate decks. His style is colorful, intricate, and full of spiritual symbolism. He is known for his skateboard decks, murals, and works like “Positive Creations” that focus on spiritual themes and personal growth.

Luis Tamani

A Peruvian artist known for his vibrant, nature-inspired psychedelic art that incorporates elements of Amazonian spirituality and Ayahuasca imagery. Tamani’s paintings are intricate, vibrant, and rooted in a connection with nature and ancestral wisdom. His paintings like “The Amazon’s Healer” and “Mother Earth” focus on interconnected themes of shamanic healing and environmental awareness.

Psychedelic Art in the Future

Today, psychedelic art has permeated both mainstream and underground cultures, evolving from posters and album covers into virtual worlds, interactive installations, and cross-disciplinary works that still embrace its roots in mind-expansion and alternative consciousness.

There are many more artists to include, and psychedelic art can, of course, extend to music, film, TV, architecture, literature and large scale installations. But here is an extensive yet non-exhaustive look at how psychedelic art has evolved over time, and the contemporary artists helping to create this change.

“Psychedelic art is not new—it is deeply ancient, rooted in the sacred expressions of nature and humanity’s connection to the cosmos,” says Archenti. “Long before the term “psychedelic” existed, cultures around the world created art as a bridge to other dimensions, a way to honor the interconnectedness of life. Today, as modern tools like AI emerge, the field is expanding in ways we’ve never seen before. AI can mirror patterns found in nature and unlock new visual languages, but it’s essential to remember that nature itself is the ultimate teacher. In the future, I believe psychedelic art will become a bridge between the past and the present, between the technological and the natural, carrying messages of beauty, healing, and balance. It will help us remember the old ways while inspiring new ones, ensuring that wisdom is not lost but reimagined in forms that honor both tradition and transformation.”

Alex Greys feels similarly optimistic about the future of psychedelic art. “I think that psychedelic art will just get better and better, trippier and trippier,” Grey says. “The more artists that are portraying the inner worlds, the more able people will be able to model and study those extraordinary realms. There is now an evolving database of Psychedelic entities and glowing celestial architectural spaces depicted by artists that will help transpersonal psychologists map the realms of archetypal consciousness.”

Let us keep “mind-manifesting” and see how psychedelic art continues to evolve and change over time.

DoubleBlind is a trusted resource for news, evidence-based education, and reporting on psychedelics. We work with leading medical professionals, scientific researchers, journalists, mycologists, indigenous stewards, and cultural pioneers. Read about our editorial policy and fact-checking process here.

DoubleBlind Magazine does not encourage or condone any illegal activities, including but not limited to the use of illegal substances. We do not provide mental health, clinical, or medical services. We are not a substitute for medical, psychological, or psychiatric diagnosis, treatment, or advice. If you are in a crisis or if you or any other person may be in danger or experiencing a mental health emergency, immediately call 911 or your local emergency resources. If you are considering suicide, please call 988 to connect with the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline.

DoubleBlind Mag Read More